There are many histories of Cleveland. Not just one history of the city. No history that would tell us, “This is the way it was.”

There are many ways to report history. It could be from the view of different people. Different movements. Different economics. Different heroes. Different villains. Different reasons why the city went this way or that way.

Now, there is a new history examining this city through the eyes of what many people might see as odd or unusual.

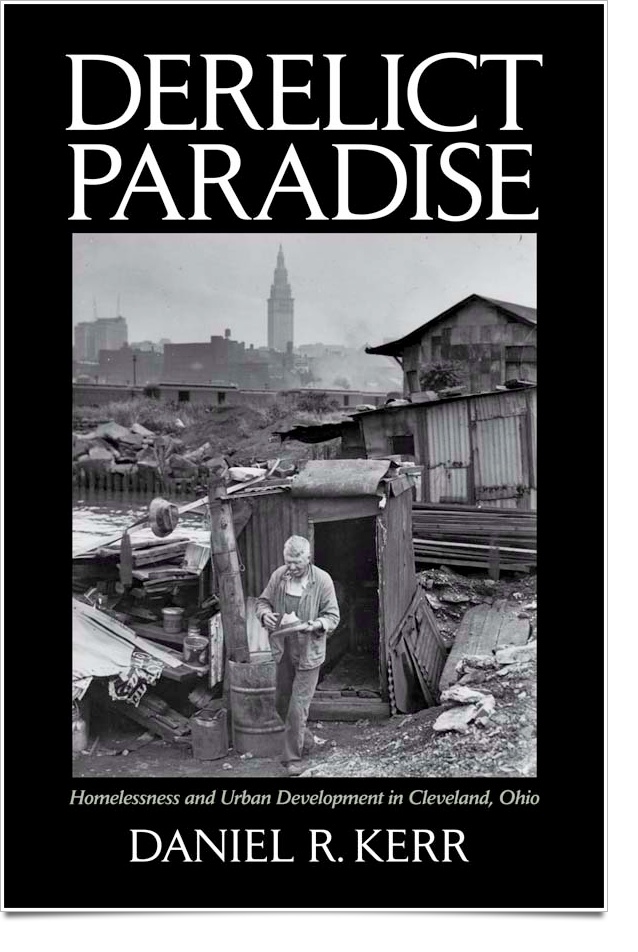

Daniel Kerr’s Derelict Paradise – Homelessness and Urban Development in Cleveland, Ohio, does this. It is a remarkable testament of how – through the city’s history – the poor (especially black poor) have been pushed aside to make way for what the wealth of the community deemed Progress.

It tests the matter of who enjoys Progress and who doesn’t.

As Cleveland media hail and promote casino gambling (isn’t the media disgusting) and a new convention center as the latest city comebacks, Kerr has some reminders that there are losers and winners. We pretty much can bet on which will be which in this contest.

Even with the Group Plan of the early 1900s, Kerr says, the demand for Progress came at a great cost to low income Clevelanders. “In 1899 the chamber (of commerce) urged the city to eliminate ‘a notorious slum’ known as the Hamilton Avenue vice district” to make way for a civic center.

“The plan the architects argued would alleviate disorder and promote harmony: ‘The jumble of buildings that surround us in our new cities contributes nothing of valuable to life; on the contrary, it sadly disturbs our peacefulness and destroys that repose within us which is the basis of all contentment,'” he wrote. Speak of elitism. Whose repose is destroyed? At whose expense?

Kerr writes “Neither the architect nor the political and business leaders that backed the plan indicated any concern for the people who would be displaced by the project.” Business as usual. Past is present.

We love to idealize past leaders. They did such magnificent things, we are told. Kerr cites one business leader complaining that people uprooted by new construction didn’t move where they should have moved, but “destroyed the value of the Erie Street Cemetery.” Such a shame! How inconvenient.

The past echoes through the years. Today we see Mayor Frank Jackson and downtown cheerleaders eager to swipe everyone without a suit and tie from Public Square for the casino owners and players. It was ever so.

“The proliferation of panhandlers on downtown sidewalks provided the most immediate challenge to Cleveland’s boosters at the onset of the Depression. The sheer numbers of people begging or selling apples, pencils and other items on the streets threatened the general sense of order that Cleveland politicians, businessmen, and civic leaders wanted to project,” Kerr writes. Yesterday and still today. Whose streets are these?

Even the 1930s had its Joe Romans and Joe Marinuccis doing the bidding of corporate leaders.

And Mayor Jackson has pledged some $800,000 to keep the casino area cleansed.

Kerr takes us through the years of rousting those who have no place to call home. In the early 1930s Whiskey Island was such a place, called at that time a “Hooverville” after the Depression President. In 1934 Mayor Harry Davis ordered eviction of the shanties built as shelter by the homeless. The Convention Bureau, he reports, wanted to sell Cleveland as “a summer spot.” Thus the bulldozing. Even the pr dreams don’t change much with time.

The book gave me a peek into Cleveland before I got here in 1965. I learned first-hand about the urban renewal disasters here. As a reporter I got to travel through some of its tragedies in Hough and other East Side neighborhoods. The Plain Dealer in the mid-1960s had full-page pieces on such problems under the title “The Changing City” and I was assigned to many of them.

One aspect of this period that has escaped notice and it may be responsible for the advances possible now in Ohio City, Tremont and Detroit Shoreway was the lonely fight Al Grisanti made to keep the destructive urban renewal from damaging the west side. Grisanti, a former downtown councilman, fought urban renewal most of his life. He was often a visitor at the PD news offices, trying to alert reporters about urban renewal dangers. One of his favorite sayings was “We got to organize the confusion.” Someone from the street couldn’t walk the news offices of today’s PD. Tight security.

Grisanti stopped urban renewal before it crossed the Cuyahoga River. It never did to the west side what it did to east side. Essentially wrecking it. Kerr tells of this disaster, too.

Cleveland, as usual, was pushed beyond its limits by an active corporate and foundation community. It had, writes Kerr, more acreage (6,060 acres) under urban renewal than any other American city.

Indeed, Upshur Evans of the Cleveland Development Foundation (CDF was created by $5 million from the Leonard Hanna fund, routed through the Cleveland Foundation) pushed or went around city government, helping cause a disaster that still reverberates. Evans, a former Sohio executive, said this, according to Kerr about urban renewal: “It isn’t a matter of social consciousness – it is a matter of plain, ordinary, practical common business sense. In short, we believe it will pay out. It means ‘pay dirt’ for Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, and northeast Ohio.” It didn’t pay out or off. Not to those who pushed it and surely not to those pushed.

I remember interviewing Evans when I was at the PD. He revealed that the business community gave a hefty sum to the City Planning Department to “plan” downtown. At the same time – behind the scenes – the development foundation was planning urban renewal. It would render the city’s plan irrelevant. I remember this because when we (me and the late Don Sabath) wrote it in an article, city editor Ted Princiotto, a lunch companion of Evans, challenged us that Evans couldn’t have said that. Both of us agreed he did. The information was muted in the published account.

One of the clearest assessments of this time was made by banker Tom Westropp who sat on the city plan commission. “For some the urban renewal program worked very well, indeed. Hospitals and education institutions have been constructed and enlarged. So have commercial and industrial interests and many service organizations, all with the help of urban renewal dollars. With respect to housing, however, the urban renewal program has been a disaster.” His last remark was most telling: “I wish I could believe that all of this was accidental and brought about by the inefficiency of well meaning people – but I just can’t. The truth, it seems to me, is that it was planned that way.”

Kerr covers one of the most despicable moves of this time. Many blacks were being uprooted by urban renewal. Little if anything was done to provide relocation for those displaced.

“Living up to its promise, CDF found a solution to the city’s urban renewal doldrums, build the relocation housing on a dump. Using slag from the blast furnaces of Republic Steel, the infamous Kingsbury Run would be filled and new housing constructed,” writes Kerr. It was a decision that highlighted the racism that helped produce protests and riots in the 1960s. People began to realize what was happening to them. They were being treated like garbage.

Kerr writes that the PD editorial board “threw its support behind the plan.”

Little changes. The ideas of the big shots are always A1 at the PD.

“Amid this state of euphoria, Cleveland’s disastrous headfirst foray into urban renewal began,” Kerr concludes. As one federal official said, “Cleveland is our Vietnam. We’d like to get out but we don’t know how.” That summed up the game played on the city’s citizens by its highest level corporate leaders.

Now, I can’t forget that this book addresses homelessness – in the past and present. His personal experience with the homeless in Cleveland prompted Kerr to embark on this book, he told me. He began this project in the fall of 1995. He started having free weekly picnics on Public Square. He reports what the homeless told him. Their remarks remind one that they know what is happening to them. And have ideas of why it is happening and by whom.

I believe he makes a strong case for why we have so many homeless people in our cities today. Anyone working in the city should read his take on this phenomenon.

Why is there and why has there been so much homelessness in Cleveland. Is this a new phenomenon, as many seem to believe? Or is it endemic, always a part of our city and how it operates?

How does homelessness happen?

If Kerr’s assessments are right – and I think they are – a lot of so-called “homeless” people are going to be especially hurt by the opening of the Higbee building casino.

From the 1880s to the 2012s little has changed. The modus operandi remains the same. Get those people out of sight. It hurts business.

Kerr reveals with strong evidence how a combination of vast destruction of cheaper housing, the development of day labor businesses that provide cheap labor at such reduced income that it makes housing unattainable. Combine this with the horrendous climate of jailing people, especially blacks, and you have a recipe for more and more guaranteed homelessness.

“The massive expansion of the penal system benefits the careers of politicians, provides profits for prison contractors, and offers secure employment for guards, while it leaves ex-offenders unable to access stable jobs or housing. Non-profit organizations that run shelter and social service for local governments benefit from the contracts they receive.

“They are not charged with eliminating homelessness; their role is to contain it,” he concludes.

Kerr notes that former Mayor, Governor and Senator, George Voinovich’s family profited handsomely by prison expansion. The family business, the V Group, between 1980 and 2000, Kerr writes, constructed over a dozen state, county and city jails in Ohio. “The firm grabbed some $100 million in contracts” in that time, Kerr writes.

With 20 percent of the state’s inmates from Cuyahoga County, “Mayor Voinovich helped support the family business by keeping his brother’s new prisons filled beyond capacity,” Kerr writes.

Voinovich also helped increase the number of homeless by eliminating general relief. Kerr cites other Gov. Voinovich moves that contributed to these problems.

Kerr also reminds us of the Arthur Feckner case when Mayor Voinovich and Council President George Forbes helped police in a botched sting deal that the PD labeled as instituting a “drug plague” at a public housing complex. It put 30 pounds of cocaine on the street.

Kerr convinces me that rather than mental illness or drug or alcoholism the prime reasons for homelessness are the conditions he cites and we have allowed and perpetuated them.

Shelters, say Kerr and the homeless he talk with, are not an answer, though they have become the institutional solution for government.

“For many, sheer existence of homeless shelters is ample evidence that our society is making a concerted effort to address the issue. This assurance allows cities like Cleveland to pour public resources into subsidizing project such as new professional sports stadium, corporate construction, and condominium and townhouse developments. This confidence in the shelter system allows the market to run smoothly,” Kerr writes.

“When un-housed people resist the conditions within shelters and the policies designed to keep them there, their actions are incomprehensible for many other citizens. The efforts are seen as further evidence that the homeless are insane,” Kerr writes in his conclusion.

One homeless man explains to Kerr: “They have torn down nearly all the low-cost housing in the city. At one time downtown Cleveland was a haven, almost a utopia, for lower income people. There were a thousand cheap hotels, and cheap rooming houses, etc. They have torn them down for different stadiums. And they’ve raised, instead of $3.00 a night hotels, there are $150, $300 a night hotels.” He says they have tried to make downtown a “playground for the rich.”

He continued: “They wanted to create a complete new image for downtown Cleveland of everyone prosperous, of everyone doing real well, so they really made a sweep on all the poor people there.”

I can personally attest to the cheap housing that no longer exists. In 1965, I came to work for the Plain Dealer, having left my family temporarily back East. I took a room on E. 18th Street not far from the PD on Superior. The street had numerous rooming houses. The cost was $10 a week. Cheap enough for even the lowest paid worker. I lasted one night. Too depressing for me. Then I went to the New Amsterdam hotel, a block or so away, for $22 a week. That too was cheap housing. But it was cheap housing. It has all been destroyed for Cleveland State University.

Kerr writes, “With billions of dollars being invested downtown and with the lakefront and Gateway projects nearing completion (now it’s Horseshoe Casino and Med-Mart Convention center), Mayor White, county officials, local foundations, and area business leaders scrambled to keep the shelters open throughout the summer to prevent 300 homeless men and women from sleeping on the sidewalks and in the parks downtown. Within days of the scheduled closing, the White administration announced that the city, county, and local foundations had raised $215,000 to keep the shelters open throughout the summer. Community Development Director Chris Warren, bristling from the criticism of advocates of the homeless, defensively maintained: ‘We should not apologize for taking on the task of keeping people off the street.’ The concerns and criticism of social service providers dissipated that winter when the federal government increased its shelter grant for the city from $309,000 to $884,000.” But to hear Kerr’s homeless voices – shelters were not the answer – unsafe, dirty and often run by people who demeaned them.

Nothing like your own home; even if a shack.

We obviously need more affordable housing, an alternative to day labor businesses that rob workers to provide other businesses with cheap labor, and a much higher minimum wage.

* * *

Daniel R. Kerr lived in Cleveland Heights, is a graduate of Heights High; has a BA from Carleton College; MA & PhD from Case Western Reserve University; taught five years at James Madison U. in Virginia and is now interior director of public history at American University in D.C. He is married to Tatiana Belenkaya, also a graduate of Heights High; a BA from CWRU and a law degree from Cleveland Marshall. They have a 14-month old daughter, Elsa Kerr. The book is published by University of Massachusetts Press and is available in hardback and paperback.

Roldo Bartimole celebrates 50 years of news reporting this year. He published and wrote Point of View, a newsletter about Cleveland, for 32 years. He worked for the Plain Dealer and Wall Street Journal in the 1960s.

Roldo Bartimole celebrates 50 years of news reporting this year. He published and wrote Point of View, a newsletter about Cleveland, for 32 years. He worked for the Plain Dealer and Wall Street Journal in the 1960s.He was a 2004 Cleveland Journalism Hall of Fame recipient and won the national Joe Callaway Award for Civic Courage in 1991. [Photo by Todd Bartimole.]

4 Responses to “ROLDO: The Long Class War in Cleveland”

Dick Peery

Roldo, about the housing on the slag heap in Kingsbury Run. When I was with the Plain Dealer in the early ’70s, I asked Growth Association head Bill Adams about a problem at the Rainbow Terrace Apartments. He told me they were built because a housing component was needed to qualify for federal money in Erieview. The urban renewal district was drawn to snake from East 9th and St. Clair to Kingsbury Run and along the railroad tracks to East 77th south of Kinsman. So the 40 story Erieview Tower and other buildings in the area were made possible by putting up a poorly built project four miles away.

Adams said the construction also solved Republic Steel’s problem of what to do about the slag heap. An added benefit for the company was that corrugated steel instead of plaster was used for the apartment ceilings. I had called Adams because snow was blowing into a vacant second floor apartment, causing condensation that dripped from the metal ceiling below. “You have to put on a hat to go to the bathroom,” the tenant told me.

I included Adams’ comments in my story, but they were taken out. I was told someone would investigate and follow up with a more in-depth explanation. It never happened.

Roldo Bartimole

Dick: It sounds all too familiar. I believe the comment I had in there by Tom Westropp says it all. That those who were doing this damage to the city, and particularly to blacks, knew what they were doing.

The city paid a heavy price and is still paying and playing the same old game.

Thanks for your addition.

G Althar

When will clevelanders “get” the idea that the way to solve the problem of the poor is education , education,education!

Roldo Bartimole

It is really not that simple.

Education requires one to be able to accept knowledge.

And too many of our people are disabled before the chance comes.